Overcoming the West

Nikolai Trubetzkoy and the Legacy of Eurasianism

Originally published in Russian as the foreword to Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Nasledie Chingiskhana [The Legacy of Genghis Khan] (Moscow: Agraf, 1999).

A Monument on “Eurasia Square”

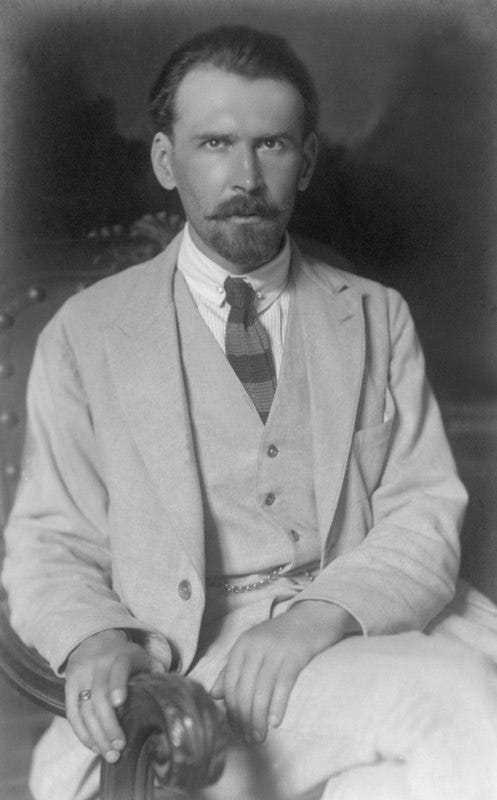

Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetzkoy (1890-1938) may by all rights be called “Eurasianist Number One.” It is to none other than him that the basic premises of this incredible, creative worldview belong. Prince Trubezkoy could be called the “Eurasian Marx,” just as Petr Savitsky clearly evokes the idea of a “Eurasian Engels.” The first strictly Eurasianist text was a book written by Nikolai Trubetzkoy called Europe and Mankind, in which the fundamental principles of an emerging Eurasian ideology can easily be deduced.

In a certain sense, it was precisely Trubetzkoy who founded Eurasianism, who discovered the primary lines of force of this theory, which would later be elaborated by an entire pleiad of the most prominent Russian thinkers – from Petr Savitsky, Nikolai Alekseev, and Lev Karsavin to Lev Gumilev. The place of Trubetzkoy in the history of the Eurasian movement is a central one. Once this tendency is affirmed as the dominant ideology of Russian statehood (and this will inevitably happen, sooner or later), it will be to him – Prince Nikolai Sergeevich Trubetzkoy – that the first monument will be erected. His will be the main monument on the future great “Eurasia Square,” swimming as it shall be in luxuriant foliage and the purest streams of silver fountains.

The Fate of the “Russian Spengler”

To speak of Trubetzkoy is to speak of Eurasianism as such. His personal and intellectual fate is inseparable from this tradition. His biography is extremely simple: a typical representative of a most famous princely line, which had yielded a panoply of thinkers, philosophers, and theologian; he received a classical education, specializing in the field of linguistics. He took an interest in philology, Slavophilism, Russian history, and philosophy. And he distinguished himself with his brilliant patriotic fervor.

During the Russian Civil War, he came out in support of the White movement and emigrated to Europe. He spent the latter half of his life abroad. Beginning in 1923, he taught in the Slavic department of the University of Vienna, focusing on philology and the history of Slavic writing. Along with Roman Jakobson, Trubetzkoy belonged to the core founding group of the Prague Linguistic Circle, which developed the bases of structural linguistics – that intellectual movement which would later come to be known as “structuralism” – during the 1920s and 30s.

Prince Nikolay Trubetzkoy was the soul of the Eurasianist movement, its main theorist, and a Russian Spengler of a sort. One should begin the history of this movement with the publication of his book Europe and Mankind.

It was Trubetzkoy more than anyone else who actively developed the principal aspects of Eurasianism. But, being a scholar who devoted a significant amount of time to his philological studies, he scarcely and only begrudgingly took an interest in the application of his theory to the politics of the day. His close friend and comrade Petr Savitsky would fulfill the role of political leader within the movement. Trubetzkoy’s temperament was more disinterested, characterized by a penchant for intellectual speculations and abstraction.

The crisis of politics in Eurasianism, which became apparent at the end of the 1920s, bore a heavy, painful toll on its main theoretician. With the consolidation of Soviet power in Russia, the contingency, archaism, and irresponsible attitude of the Russian emigration, and the spiritual and intellectual stagnation which took hold in both branches of Russian society in the 1930s following the spiritual cataclysm at the start of the century, Eurasianist ideology, founded on a plethora of the subtlest intuitions, paradoxical epiphanies, and passionate flights of political imagination, had come to a dead end. Seeing how Eurasianist ideas were being marginalized, Trubetzkoy dedicated his last years all the more to pure scholarship: he stopped participating in the polemics and conflicts within the movement after its schism, and he turned a blind eye to the criticisms of Eurasianism coming from its enemies in the Russian emigration — undoubtedly the product of ressentiment. In 1937, in Vienna, Prince Trubetzkoy was captured by the Gestapo and spent three days in jail. During this time, the aged scholar suffered a stroke from which he never recovered and died soon after.

His death went practically unnoticed. A terrible catastrophe came over the world. Its main ideological tenets were a rejection of those principles and axioms which the Russian Eurasianists and their European analogues – the proponents of Conservative Revolution, National-Bolshevism, and the Third Way – had managed to formulate on the highest level of spirit and with the greatest intellectual effort.

The Eurasianists foretold with prophetic foresight the paths which future worldviews would take and the politics that would result therefrom. But, alas, the fate of prophets has been the same in every age: stoning at the hands of a mob, burning at the stake, expiration in the GULAG, or fatal imprisonment at the hands of the Gestapo…

Continue:

Really strong piece on Trubetzkoy's intellectual legacy. The comparison to Marx and Engels works perfectly for showing how foundational his thinking was to an entire ideological movement. I'd never considered the tragic irony of him being captured by the very forces that rejected what he'd formulated, only to die unnotticed. That detail about the stroke after three days in custody hits differnet knowing the rest of the movemnt's history.